Note

We are back, and this time, we are pleased to bring you our second guest post. It was written by Enyinnaya Uwadi, who is currently a Commonwealth Doctoral Scholar in Competition Law and Emerging Markets at the University of East Anglia. He has also written many articles on Nigerian competition law. You can check them out here.

As always, thank you for your support, and we hope you enjoy this week’s article.

Guest post – After the Reggae, Play the Blues: A Message to Dominant and Multinational Businesses

The title of this article,1 finds root in Harrysong’s 2015 hit song, “Reggae Blues.” In this article, ‘reggae’ represents anticompetitive and unregulated business practices while ‘blues’ represents playing by the rules within a competition law regime.

As you must know by now, competition law is a legal system that regulates business practices by prescribing acceptable (or pro-competitive) conduct and penalising harmful business practices, like cartels, price-fixing, abuse of dominance, etc. Its purpose is to address market distortions and promote competitive markets.

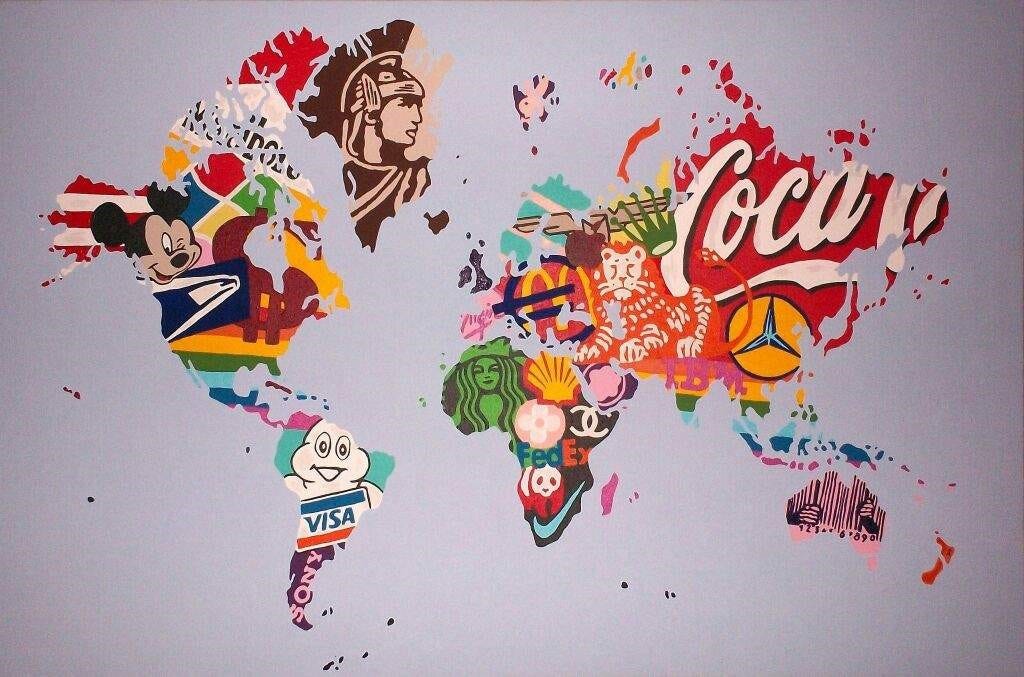

With an American origin, competition law has been adopted by several countries in their attempt to address market imbalance, promote economic development, and protect consumers. By the end of the last century, several developed countries had already enacted competition laws, while their developing counterparts, especially those on the African continent, lagged. The predictable outcome of the huge divide was that the continent became a breeding ground for big businesses and multinational firms to practice their reggae moves. With dreadlocks being synonymous to reggae artists: the lack of competition law watered and spiralled the growth of their dreadlocks, so much so that it grew wild beyond a reasonably acceptable length, but only within the African continent.

The reggae music played so loud to the detriment of the listeners, as well as music lovers to the extent that several countries on the continent saw the need to change the music to blues as they moved from command to market economies toward the late 1990s and early 2000s. As of January 2019, several African countries including Africa’s big 3 economies (Nigeria, Egypt, and South Africa) had enacted comprehensive laws that regulated anticompetitive business practices. South Africa led the pack with its Competition Act 89 of 1998, followed by Egypt with the Law on the Protection of Competition and the Prohibition of Monopolistic Practices, Law No. 3 of 2005, and lastly, Nigeria with the enactment of the Federal Competition and Consumer Protection Act of 2019 (FCCPA).

The ascension of Nigeria to the cadre of countries with competition law is very significant both regionally within Africa and globally. With its consistent ranking as Africa’s biggest economy since 2014, coupled with the country’s population of over 200 million which positions it as the most populous African country and a global investment destination, its competition regime will most likely portend huge implications for dominant and multinational businesses across the world who hitherto, had become accustomed to reggae music while operating in Africa generally and Nigeria in particular. With the new competition regime, it is believed that a riot act has been passed, banning reggae and compelling businesses to stick to blues, with a sheriff in the form of the competition authority ready to bare its fangs on defaulters. This forms the background for the title of this article.

With the advent of the FCCPA, several changes are expected in the way and manner businesses activities within (or which have an effect within) Nigeria are conducted.

For starters, dominant and multinational businesses and their directors who, before now, operated anticompetitively and foreclosed small businesses and potential rivals to retain and grow their customer base must change their manner of operation. The dance tune has changed to blues because the FCCPA protects domestic small and medium businesses from unfair market practices of dominant firms, like bid-rigging and predatory pricing (also known as a price war).2 Such businesses must adopt and implement practices which are competition law compliant. And this must be done out of necessity because both the violating firm and its directors can be held criminally liable for anticompetitive practices under the FCCPA.3

There are also offences in the FCCPA that the average employee can commit. These include obstruction of investigation; offences against documents like destruction, falsification, alteration or withholding of documents; giving false or misleading information; and failure to appear or give evidence before the competition authority during investigations.

Therefore, this calls for proactive measures by dominant and multinational businesses to create a competition compliance department or increase the mandate of their existing compliance units by employing new officers who are trained in competition law, especially on abuse of dominance, as well as reviewing horizontal and vertical agreements that could have anticompetitive elements. This will ensure that these businesses are regulatory compliant and up-to-date with competition law standards.

Also, there is a need to promote competition culture and create competition law awareness within all strata of a business through a regular emphasis on the consequences of anticompetitive business practices. This will forestall or mitigate the risk of a member of staff’s inability to resist the allure of reggae. This is especially relevant in the context of dawn raids (unannounced early morning raid of a suspected company’s premises by the competition authority to interrogate staff, inspect, and confiscate relevant documents and devices for an investigation) where every staff is expected to cooperate with the competition authority. The uniqueness of dawn raids is that the authority is most likely to speak to, and obtain information from, lowly ranked members of staff because usually, those at the top cadre seldom resume work at dawn. It is therefore imperative for businesses to develop a comprehensive internal competition culture that cuts across every stratum of staff to ensure that only relevant, non-implicating information is divulged in the event of a dawn raid.

Dominant and multinational businesses should endeavour to play to the blues and do all within their means to resist the urge of going back to their old ways. Irrespective of the fact that the competition authority is still in its infancy days, it has developed sufficient teeth and is ready to bite. Examples of recent competition law enforcement against powerful companies like Google abound in foreign jurisdictions. Close by in South Africa, Computicket, a ticketing company, was fined in 2019 for abuse of dominance.

Ultimately, anticompetitive conduct presents a new business risk to dominant and multinational firms which can be avoided with the right structures and practices in place. Strict compliance is, therefore, a sine qua non; otherwise, businesses may be exposed to both civil and criminal penalties, which have the potential of running the businesses aground.

Play blues, not reggae.

Before you go…

…here are some recent developments in the world of competition law:

School uniform: The Competition Commission of South Africa (CCSA) recently issued guidance on school uniform—yes, you read that correctly. The CCSA has urged schools to ensure that uniform is as generic as possible, so that it can be obtained from as many suppliers as possible. This would allow more suppliers (offering a range of prices) to compete, which would give parents more choice. Schools are also discouraged from mandating that uniform must be bought from specific suppliers, but where this is unavoidable, these suppliers must be selected after a competitive bidding process, and the school must continually ensure that the supplier is actually offering competitive prices. CCSA officials have been visiting schools to raise awareness and to encourage headmasters to sign agreements to enforce the guidance. No sector is immune from anti-competitive practices.

Transparent lending: Quite an old development from late last year, but one that is worth noting nonetheless: the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) compelled mobile digital lenders to disclose their terms before disbursing loans to borrowers. The CAK had conducted a study which found that only 27% of digital borrowers were aware of the fees and costs of other digital loan providers, and also that more than 70% of people have, at least once, failed to pay digital loans on time. So, by mandating disclosure of terms, the CAK will make the lending space more transparent. In all, this aims to tackle the problem of predatory lending by allowing borrowers to make more informed choices, while also attempting to reduce the number of defaults in the digital lending space.

This article was previously published on Business Day, but it has been edited slightly for Compedia.

This is a practice whereby businesses temporarily reduce product prices below the average market price in an attempt to increase their customer base and foreclose rivals and upcoming businesses who may not be able to afford to sell below average market price.

See Sections 69(2), 74(2), 107(4)(c), 108(3)(c), 109(3)(c), 111(2)(c), 112(c).